June 30, 2020 GraphQL Apollo Client NodeJS Serverless Development

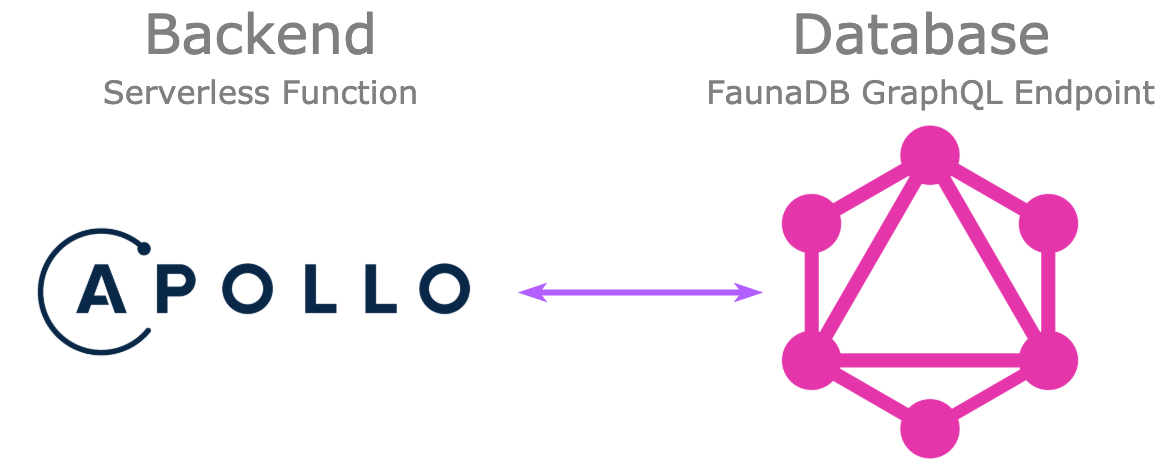

During development of the dashboard I’m making for ClaimR I found myself in the position where I wanted to query a GraphQL endpoint from my backend. (It’s a NextJS powered project, hence the server sided logic is written in Node.) So, I started looking for GraphQL clients but with little success.

graphql-request seemed like a match, with what looked like a recent release earlier this year. However, on closer inspection it’s pretty clear that it has been abandoned. In other words, not a proper foundation to build my new product upon. I came close to resorting to making plain HTTP requests myself, until I stumbled upon Apollo Client’s feature allowing you to make queries yourself!

Apollo Client advocates in their documentation that it’s primarily for React, thus strongly pushing everyone to use their hook based architecture. Recently I have been using Apollo Client frequently for consuming GraphQL in frontend projects. However, this new project required consuming GraphQL on the server, therefore the React use-case didn’t apply.

Behold, we can actually use the Apollo Client on server side. The documentation doesn’t mention this anywhere, and the client is actually branded as “Client (React)”. However, on the Getting Started page of the documentation, they start by using client.query(...) before they introduce hook and component based requests.

The options from client.query(...) and client.mutate(...) are very similar to the useQuery and useMutation we know from React. Both return a promise, which include the response, error and the like. Here’s a little example to show roughly what it looks like:

defaultOptions of the client is configured to disable the cache. This is completely optional, however the default caching policy is reasonable for usage on the frontend. However, this default caching policy in the backend results in multiple issues in the backend.

For starters, your backend will start working with stale data. So in all likeliness, it will also start returning stale data. To make matters worse, during development hot-reloading will purge the cache every time you make a change to your backend or deploy a new version. Thus, at first glance it could all look fine, only to become an issue when you start working on something else.

I burned my fingers by having (unintentionally) client side and server side caching enabled — both are using Apollo Client. Figuring out where the stale data originated from was tedious, as you need to manually inspect the query responses. In addition, it’s very easy for another developer to not be aware of this server-side caching behavior, which will surely drive them mad when debugging.

Here and there I overwrote the fetchPolicy for individual queries to use caching, if I was certain that the response wouldn’t change. For example, there’s one query on one write-only field which can safely be cached. I’m still not too thrilled about it, but works for now and improves both performance and resource efficiency. However, violation of the implicit assumption about the query results being write only will cause incorrect behavior.

So the rule of thumb on enabling caching is simple, when in doubt, don’t. Instead, focus on client-side caching wherever possible.

Enable caching? When in doubt, don’t.

Another issue that emerged as I deployed my backend as a serverless function, was data inconsistency. Each instance deployed by my serverless provider had its own cache, hence different instances would cache different data for the same query. To the user, this caused the data to flicker, as requests were routed to an instance at random, causing responses from different instances to contain different results.

Also, expect increased memory usage, as all responses are stored in the cache by default. This could quickly become an issue if you deploy your backend onto many small instances, as this cache will start to take up quite a bit of memory fast.

Lastly, this form of local caching will see degraded effectiveness when a lot of instances are used or instances are purged often — as would be the case in serverless environments. More instances mean having more individual caches, thus the chance of having a cache miss increases with more instances. In the end, the same data needs to be cached multiple times in order to get many cache hits.

To conclude, be mindful about caching. It can help a bit, but the default Apollo Client caching implementation is in memory and consequentially not as effective as it is on the client side. Maybe in the future we will see a Redis client, as exists for Apollo Server, but until then, we will have to make due with what we have.

Thank you Keira Nicole Soutar for taking the time to review this post.

This post is now also published by “The Startup” on Medium!